TOKENS OF THE SOMERSET COALFIELD

Background

The Somerset coalfield was small by national standards, consisting of around 240 square miles in the north of the county. Early coal gathering (from at least mediaeval times) consisted of pickings from surface outcrops and adits, and then mining from shallow bell pits. However, from the time of the industrial revolution (late C18) underground (or deep) mining commenced. It was around this time that William Smith (sometimes known as the “Father of English Geology”) came to live in Somerset and, working for local coal producers, published the first detailed geological map of Great Britain.

Although infrastructure such as track and tramways, the Somerset Coal Canal, and railway links were built to transport output from the Somerset collieries, their coal never established a market outside Somerset (and to a lesser extent, Bristol), so in practice its usage was almost entirely local.

The most productive years for the coalfield were around the beginning of C20, but productivity went into sharp decline after WWI. In 1901 there were around 79 active collieries, but when the industry was nationalised in 1947 there were only twelve, with half of those being closed soon afterwards.

In general the coalfield was small, with many geological faults which complicated economical coal getting. Most of the best seams were already being exhausted in the first two decades of the C20, and thereafter most remaining seams were often very small, making them uneconomical for investment in modern mining methods and equipment. The last mine closed in 1974.

Recommended reading;

“The History of the Somerset Coalfield”, a detailed account by C.G.Down and A.J.Warrington,

“Collieries of Somerset and Bristol”, a richly illustrated publication by John Cornwell

The Tokens

Nationally, mining tokens have been used prolifically for a wide range of purposes (notably for recording the extraction and transportation of coal in various different circumstances, but also as quasi-money in small communities), but the surviving tokens from Somerset appear to have served as personal checks for individual miners (referred to locally as tallies).

Nationally this usage appears to have begun in the second half of the C19, but it was not universal at that time. The background to their more widespread introduction was that underground mining was very dangerous work, with accidents and loss of life all too frequent. Most of these were caused by close working with dangerous tools in cramped conditions, but wider causes included roof collapses, poisonous gases, fire and flooding.

However, when serious accidents happened underground there were limited (or no) procedures for understanding the nature of the immediate problem and undertaking rescue and remedial actions. Often it was not even known whether, or how many, underground men might have be affected. For example, when an underground explosion occurred at Norton Hill colliery in 1908 it took ten days to establish that ten men had been killed.

The Coal Mining Act of 1911 introduced many new safety measures, including highly trained First Aid crews. At that time the adoption of the personal check system was still not widespread, but it became mandatory in 1913 with a supplement to the 1911 Act, requiring checks with the name of the pit (or its owner) to be individually stamped with the number of each miner, and to be retained by him while underground (coincidentally 1913 was the year of the worst mining disaster in British mining history, when 439 lives were lost in an explosion at the Universal Colliery, Senghenydd, South Wales).

While some collieries would have already issued personal checks stamped with the individual number for collecting pay, the new development was that the check should be stamped with the individual miner’s number and the same number was also stamped onto his safety lamp; the pairing of the miner’s name and his number were duly recorded in the office or lamp room and on a daily basis there would be knowledge of where men were deployed. The value of his this practice was that in the event of a catastrophe underground the workers on the surface could use the checks to establish who was underground and in which area, and the miner there would be in possession of the corresponding check. Over time the two check system (one to be kept above ground, the other retained by the miner himself) became standard procedure. Before such practices existed, there would be confusion about how many, and which, miners might have been caught up in a catastrophe, with obvious implications for rescue efforts. The check system would enable rescuers to target their efforts and account for every missing miner.

Here is a selection of Somerset mining tallies, all believed to have been carried by individual miners for pay and/or lamp registration.

Camerton Colliery: 1800-1950

Dunkerton Collieries (1906-1925)

Grayfield Colliery, owner; Earl of Warwick (1833-1911). Found on the colliery site.

Greyfield Collieries (1833-1911). Found on the colliery site. The different spellings are also found in contemporary written records.

Greyfield Colliery, Earl of Warwick (1833-1911) pay check

Greyfield Colliery Earl of Warwick (1833-1911) same pay check with a probable replacement check EW, stamped 94 on the reverse, and found on the colliery site

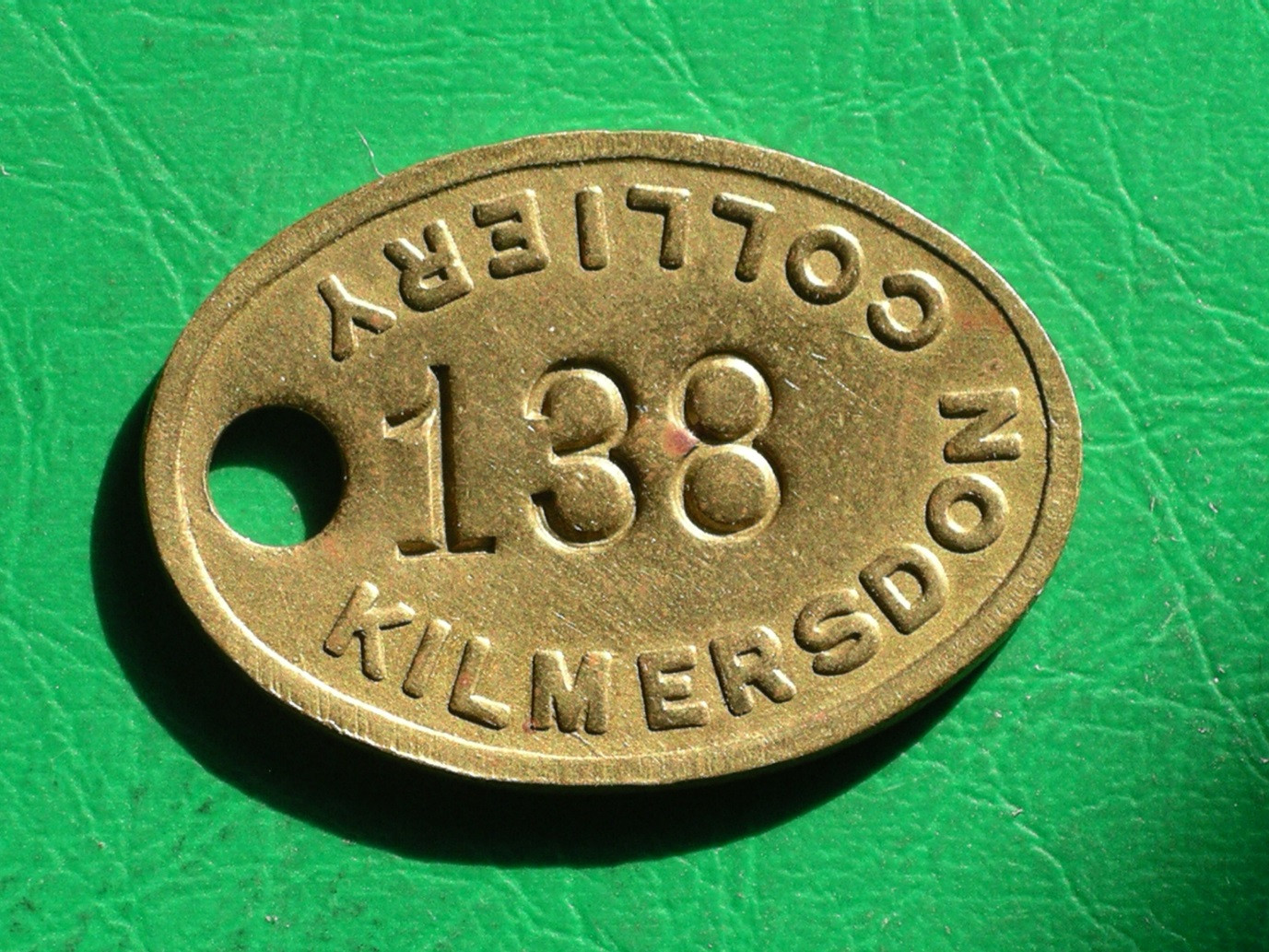

Kilmersden Colliery (1874-1973) oval

Kilmersden Colliery (1874-1973) rectangle

Mells Collieries (1863-1943) found on the colliery site

Mells Collieries (1863-1943) no colliery name, but found on the colliery site alongside named checks (note the number punch similarities).

Radstock Collieries (c1800-1954)

Personal check of Charles Frederick Newth, who worked at Braysdown and Camerton collieries. The provenance of this check is undoubted, but it does not bear the name of any colliery (so presumably pre 1913) and the significance of the numbers is not clear

If you are interested in local mining checks and tokens, or have any, please feel free to contact us (mike [at] bathandbristol-ns.org.uk).